Read Aloud and Dual Coding to Build Comprehension

My experience has taught me that reading aloud to students can be a very valuable tool to build comprehension skills in students. We know how important reading aloud is for younger students, so why is it that as they get older this practice seems to diminish and fade away? We may feel time pressure to follow required curricula or it may seem like students aren’t listening when they ask to draw while you read. I have put this to use.

First I chose a book they can’t read for themselves. Recently it has been an Alex Rider book earlier a Harry Potter book. For 4th graders with very low reading scores and very limited vocabulary so this may seem very ambitious, but just because it is above their reading ability does not mean it is above their interest level.

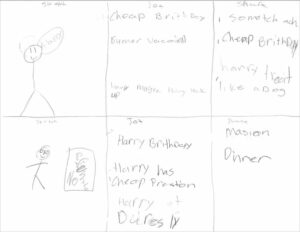

Next I structured their drawing. To start with I had them fold a paper in half lengthwise then fold it in fours leaving 8 squares. Room for a “sketch” box on the left and a “jot” box on the right. For each chapter they were to draw one thing in the “sketch” box and then write three key words or phrases in the “jot” box.

We continued this for a few days. I then asked them to fold their paper in six sections, three across. Now they did their sketch and jot, then found a classmate to share with. Any jots the classmate had that they did not were then added into the third “share” box. I also had them add a caption or labels to the “sketch”.

What I was able to point out to the students is that the “sketch” box contained the main idea of the chapter and the jots were the supporting details.

I also provided copies of the book for the students and they were able to go back and reread to find the detail they didn’t quite remember or may argue about with their friends. These students all read well below grade level and are unable to pass a written or multiple choice comprehension test, but they are now able to find the main idea and important details in literature and defend their choice.

In our school we are required to do daily fluency practice and have our students chart their progress. Some make progress in the number of words they can read in a minute but but many do not and comprehension has stayed low. What I have noticed is that when they are able to understand what they are reading they are better able to predict the coming text and their fluency increases. This is not immediate as at first they slow down in an attempt to get meaning from their reading, something that was not measured in their graph and therefore not valued. After a brief period of decreased fluency, it often increases dramatically. As their comprehension increases, they are better able to predict what is coming. So while it is often argued that a student must have fluency for comprehension, I argue that they must have comprehension for any meaningful fluency.

To put a slightly different spin on the ideas Robert Coe talks about in Classroom Observation: It’s Harder Than You Think, we end up valuing what we can measure rather than finding a way to measure what we value. Reading aloud to students of all ages has value that is difficult to measure whereas number of words per minute can be easily measured but is only a proxy for learning.